A Peconic compound pays homage to a turn of the century art colony.

The main house in Rachel Rushforth-Worrell and Andre Worrell’s Peconic compound goes by more than one name. Sometimes the couple and their teenage son, Drake, follow local custom and call the 3,200-square foot structure, which was built in 1867, “The Old King Farmhouse,” after William Henry King, an early occupant. Other times they call it ‘The Grey Lady,’ a nod to what Rushforth-Worrell describes as “the sense of a nurturing presence” in the four bedroom bolthole.

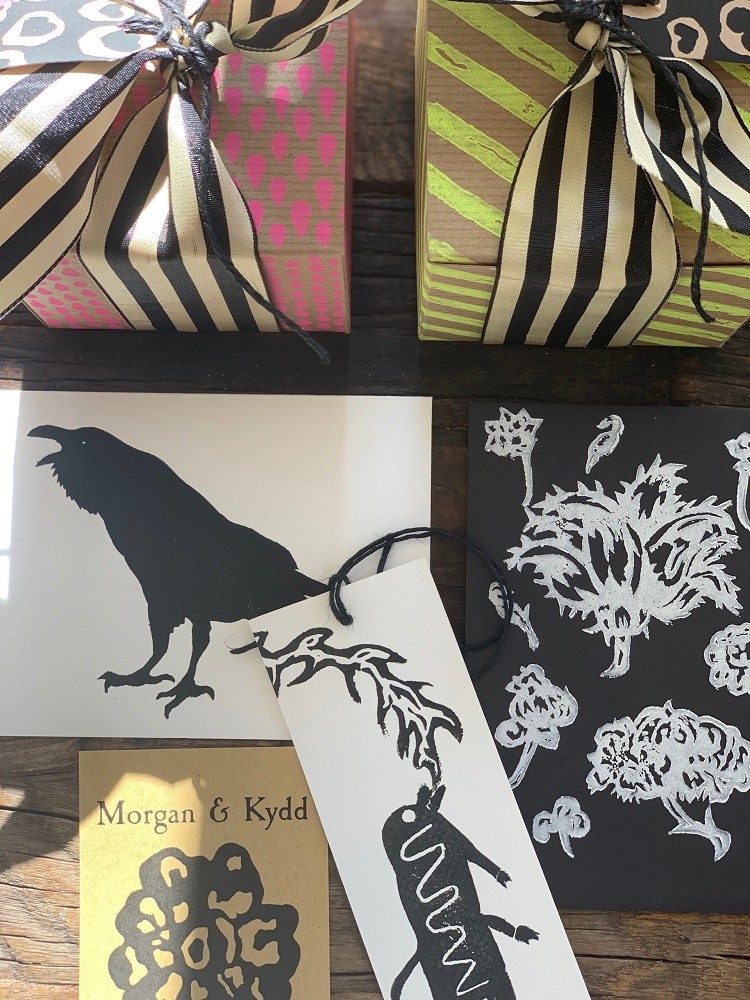

In just two years, the couple have transformed the compound into a rural escape, a workshop (for Morgan & Kydd, their handmade greeting card, wrapping paper, and home fragrance business) and their family seat.

Originally from the UK, Rushforth-Worrell acquired her design credentials and project management expertise by way of the New York fashion industry, designing clothes for the likes of Donna Karan New York and Victoria’s Secret. In 2017, inspired by The New Homesteader, an account of one family’s experiment in sustainable living, she and Andre, a musician and an artist, fell in love with the house and traded their views of Manhattan tenements in the East Village for the open vistas of the North Fork. “We followed our instincts and took a leap of faith,” Rushforth-Worrell says. “The book was our guiding light.”

They were also guided, after a fashion, by the turn of the century figurative painters Henry and Edith Mitchill Prellwitz. Intrigued by the many Arts and Crafts details in the house, including a carved staircase, Rushforth-Worrell did some research and learned that the Prellwitzs had lived there in the early 1900s before moving to a house down the road. She and Andre were also inspired by the merchants and farmers and indigenous people — especially the indigenous people — who preceded them. At the local historical society, Rushforth-Worrell came across an old map that showed teepees which, by her reckoning, appear to have been situated within shouting distance of their property. “Whenever we went down the road to the beach, we’d ask ourselves, ‘What century are we in?’” She adds, “We’d look at the mature plantings in the garden and feel a sense of history.”

The compound, which includes an art studio and attached apartment (winner of this year’s Hamptons Cottage and Gardens’ Small Space Design award) reflects that history as filtered through the pair’s own modern sensibility. There’s a library with reading nooks, beamed ceilings, period ornament, and millwork of unknown yet historic vintage, probably executed by artisans at the Prellwitz family’s behest; a sitting room with sofas upholstered in durable white duck; and a long farm table in the south-facing sunroom that Rushforth-Worrell paired with white bucket chairs, reproductions of the Italian design firm Sintesi’s iconic Orbit chair. Other rooms are furnished with antiques that Rushforth-Worrell brought over from England.

One plank of the couple’s sustainability plan — financial, that is, rather than environmental — entails making the house available for seasonal rental. Another plank is Morgan & Kydd, which they run from the art studio. Rushforth-Worrell painted the outside walls in Benjamin Moore’s Westcott Navy. She liked how the shade chimed with the gunmetal-finish of the aluminum-clad windows — historically-precise replicas of the originals, which date from the early 1900s. “That navy hue is actually a historical color. It looks so beautiful against the green of the garden,” she says. Inside, the exposed beams on the high ceilings are original. (“They were orange when we got here. We had the contractors sand them down four times before they bleached them!”) There’s also a working fireplace and, unusually, what looks to be a small stage, complete with a built-in seating area. Rushforth-Worrell surmises that the artists may have brought in performers from the city for entertainment. As it happens, one of Henry Prellwitz’s paintings is titled “Road Home” — not a bad metaphor for the couple’s project. As Rushforth-Worrell puts it, “We wanted to breathe creative life and energy back into the property.”