It’s one o’clock on a Tuesday afternoon, and Frank DeCarlo is in the kitchen of his lower Manhattan restaurant, Peasant, preparing for dinner service. On most days, the kitchen is where you’ll find him, never far from the massive hearth that is the restaurant’s center of gravity, which he built with his own two hands.

If his name doesn’t mean anything to you, DeCarlo’s indifference to the public relations game might have something to do with it. At a time when chefs are the new rock stars and restaurants are run like outposts of corporate empires, the white-bearded chef remains defiantly old school. But if you were to solicit the opinion of the highest-ranking members of the culinary elite, they would tell you that DeCarlo is royalty. Alain Ducasse counts Peasant among his favorite restaurants in New York. Paul Bocuse digs it too. And then there’s Daniel Bouloud, who celebrated his fiftieth birthday at the restaurant with a menu that included wood-roasted sardines.

DeCarlo deals in subtle, elemental flavors. He cooks with great restraint, the better to play up the qualities of his superior ingredients. At Peasant, a whole wild orata, or sea bream, will arrive at the table with crisp skin and moist flesh after a brief tour of the wood oven. Perfectly seasoned, drizzled with new season’s olive oil, and garnished with little else, it is sublime. In the spring, gnocchi might share a plate with ramps, sweet peas, morels, and a quantity of brown butter. There are no extraneous ingredients in a DeCarlo dish. Stylistically, such cookery is the polar opposite of the big over-determined flavors and elaborate presentations that seem calculated to grab the attention of smart phone-distracted diners.

“A chef in pursuit of Michelin stars wouldn’t cook orata in that simple way,” acknowledges DeCarlo. He’s right. Think of the grill restaurant Etxebarri, in the Basque Country, a site of gastronomical pilgrimage that is Michelin star-less. “I’ve had people express surprise to be served a mere piece of fish,” DeCarlo continues. “Well, orata is a very delicate, subtle-tasting fish, and you don’t want–I don’t want–anything to interfere with its flavor.”

Learning how to manipulate the heat of a wood oven when dealing with such delicate proteins as seafood can be a life’s work. DeCarlo is a Jersey boy who learned his craft in Italy. He grew up in suburban Mountainside where the local pizza parlor sold outsize American-style pies by the slice, and the dining room had red leather banquettes and smelled of nothing. After an early stint as a line cook, at the storied Il Cortile in Little Italy, he fetched up in the southern Italian town of Mola di Bari, on the Adriatic sea, and landed a job at Niccolo Von Westerhout, a local restaurant of serious repute. It was the late 1970s, and in those years gas and electric-fueled ovens were rare. Some townspeople had wood ovens in their homes; many took their focaccia and breads to be baked in a communal oven. At night DeCarlo would go fishing with the village men, using lamps and wooden bats, and then they would clean and cook their catch over hardwood and occasionally fruitwood. There were moscardini, diminutive baby octopi, and ricci di mare, or sea urchin, and young cuttlefish. “I was a kid from New Jersey!” he recalls, waving his tattooed arms. “I fell in love with Bari–the sea, the farmland, the simple way of life–and with the mystery of wood-oven cooking.”

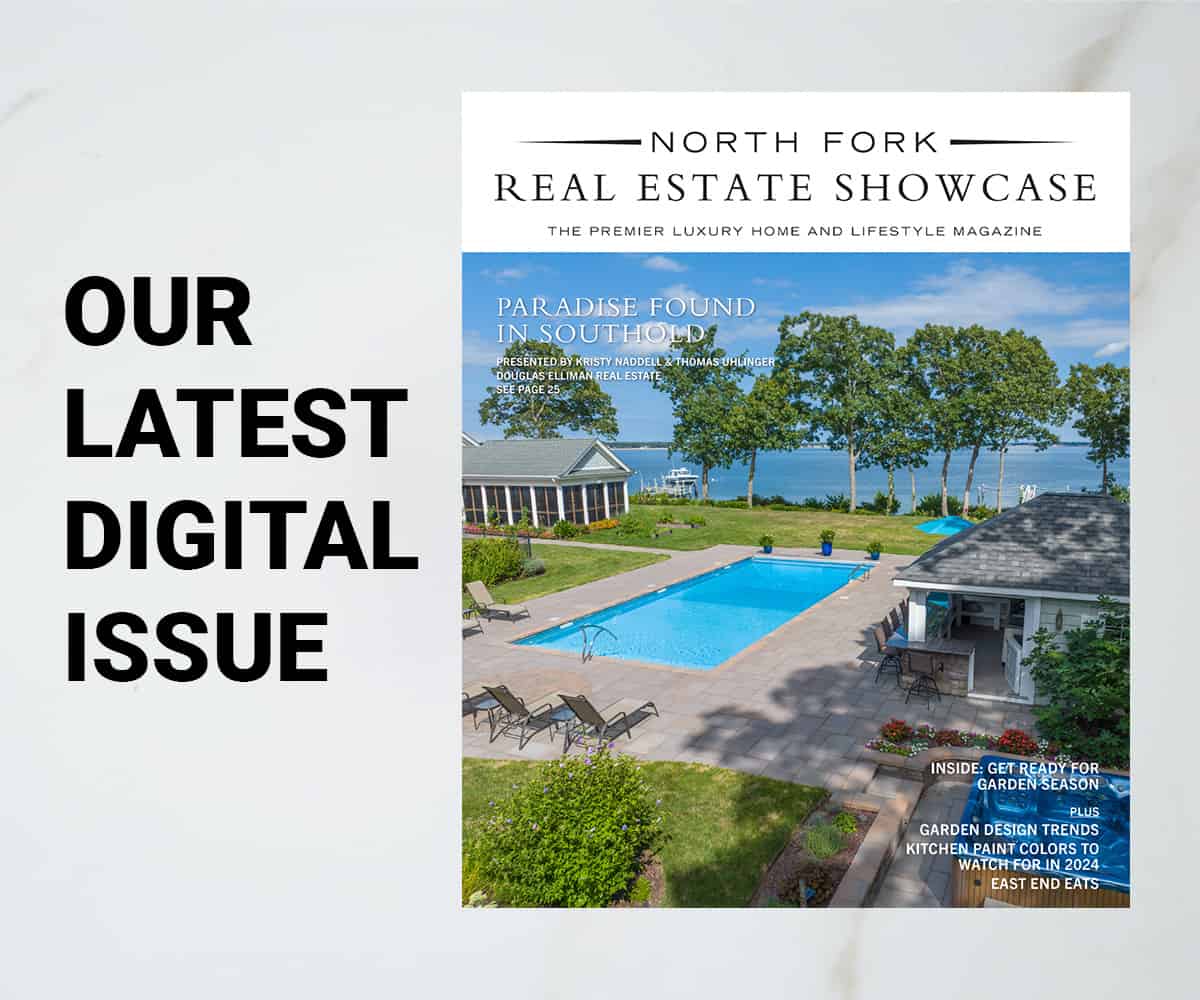

Over a decade ago, he discovered the North Fork and fell in love anew. He and his business partner-wife, Dulcinea Benson, keep a weekend place on Shelter Island, and the couple think of the area as home. Not long ago, DeCarlo heard that a waterfront restaurant in Greenport was for rent. The catch was that the wooden building, which sits on a pier and was built as a storehouse by the U.S. Navy over a century ago, needed a great deal of structural work. Having long had his eye on the historic venue–ever since it housed the now-shuttered Scrimshaw Restaurant–DeCarlo was undaunted. At this writing, Barba Bianca is scheduled to open by Memorial Day weekend.

For now, there won’t be a wood oven at the new restaurant. (“I want to preserve this structure for the ages, not, God forbid, burn it down.”) But he’ll have a charcoal grill, and he intends to source his ingredients from local farmers and fishermen and foragers. The menu will focus on seafood and vegetables, and it will be inspired by the changing seasons.

The new restaurant’s name is a nod to the pirates whose boats once lurked in Greenport’s harbor, and also to its chef, who has earned every one of the white hairs on his beard. Lamenting the proliferation of so many self-styled ‘chefs,’ he paraphrases the great Alain Passard, who once said he didn’t become a chef until he was in his sixties. “Ducasse said the same thing, and I see it that way, too,” he says, before he disappears back into the kitchen. “I’ve been cooking since I was fourteen years old. I feel like a classical pianist who’s been sitting on a bench, practicing twelve hours a day, for the last forty years.”